National, Politics, U.S. Senate

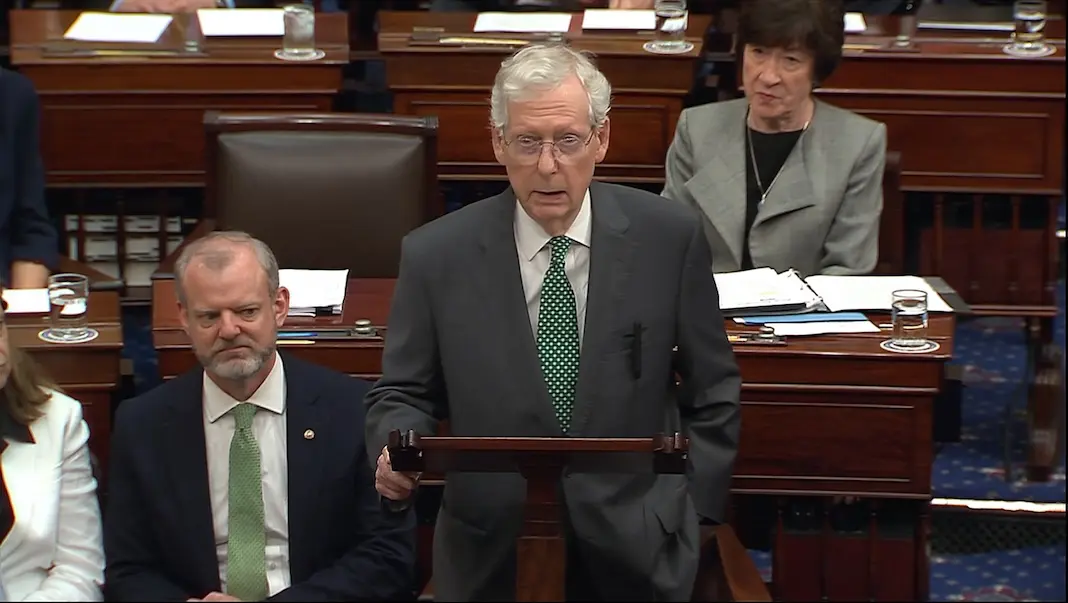

Senate majority quashes Mayorkas impeachment due to lack of specified crimes

National, Politics, U.S. Senate

National, Politics, U.S. Senate

National, Politics, U.S. Senate

National, Politics, Repro Rights